“In the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem.” Matthew 2:1

Herod the Great was best known in the Bible for his encounter with the Magi, who followed a star to find the King of the Jews (Matthew 2). His jealousy over any possibility of someone other than him being the king of the Jews enraged him and caused him to have every male child under the age of two killed.

Herod’s cruelty did not stop with killing innocent boys. He also killed members of the Sanhedrin and anyone he suspected of planning a revolt against him. He even executed many of his family members based purely on hearsay.

Everything Herod did, including his construction projects, was over the top and always to extremes. His madness (indeed, mental illness) and lust for power spilled into every facet of his life. But he was not alone in his madness. It was a common thread that ran through his entire family.

Antipater, Herod’s Father

Herod’s family originated in Edom (also sometimes called Idumea), a Jewish and Esau-descended tribal area south of Judea in present-day southern Palestine. The Hasmonean Empire ruled the area following the Maccabean Revolt in 167 B.C. Consequently, the Hasmoneans forced Herod’s family and all Edomites to convert to Judaism, which is why Herod often called himself a half-Jew.

Herod’s father and grandfather, both named Antipater, served the Hasmonean king as military commanders in Edom. Herod’s father solidified his standing by marrying the daughter of a Hasmonean noble, thus establishing that Herod and his siblings were of Arab origin but also so-called practicing Jews.

Antipater often altered his behavior based on the political climate of the time, including switching his allegiance to the Romans after they attacked the Hasmoneans and conquered Judea. Such political morphing was a skill he passed down to Herod.

Eventually, Antipater gained enough favor in Rome that Julius Caesar granted him and his family Roman citizenship and named him the procurator of Judea in 47 B.C. He held the post until he was mysteriously poisoned in 43 B.C. But before his demise, he craftily used his authority to name his son governor of Galilee, where Herod wasted no time in asserting and accumulating power.

Herod, “King of the Jews”

Not long after he arrived in Galilee, Herod decisively put down a rebellion and imposed strict rules to dissuade any further dissent in Jerusalem. His harsh tactics in keeping order captured Rome’s attention and gratitude, causing the Roman Senate to name Herod “king of the Jews,” a title he proudly wore.

Naturally, the Jews categorically rejected such a title, especially since Herod was not the king of the Jews (earthly speaking). The last Hasmonean king, Antigonus II, still claimed the throne of Judea. And his alliance with the Parthians (modern-day Iran), who were enemies of Rome, enabled him to continue holding the throne.

The Parthians eventually invaded Syria and Palestine, causing Herod to flee to Rome, where he divorced his first wife and married a Hasmonean princess named Mariamne. Though the marriage was designed primarily to create an alliance with the Hasmoneans, Herod, nevertheless, viewed the princess as the love of his life. Despite his affection, his loyalty to Antigonus was very short-lived.

After Caesar’s assassination in 44 B.C., Herod used his political savvy to secure favor with incoming dictator Octavian and his powerful Egyptian friend, Marc Antony. As a result, six years later, Antony sent out his legions to help Herod defeat the Parthians and Antigonus in 37 B.C.

Herod later executed a former and elderly Hasmonean king, John Hyrcanus II, in 30 B.C. over the suspicion he was plotting a coup. To further solidify his power, Herod executed Mariamne’s brother, an eighteen-year-old high priest, by drowning him in the palace pool out of fear that Rome would install him as king.

Following his conquest, Herod claimed the Hasmonean throne once and for all. And so, Herod began his 33-year rule as the Roman king of Judea.

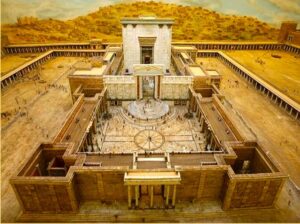

A model of Herod’s rebuild of Solomon’s Temple.

Gaining the Jews’ Favor

As much as he valued overseeing and protecting the Jews, Herod managed to anger many of them. He abolished the hereditary requirement to be a priest (one no longer had to be a Levite, thus breaking Torah in Exodus 28). He killed 46 members of the Sanhedrin, built temples dedicated to the Roman emperor, pushed the people to accept Roman customs and sporting games, such as the Olympics, and he was always in opposition with the Pharisees. Herod also established an internal spy network and eliminated anyone suspected of planning a revolt.

Nevertheless, Herod tried hard to curry his restless subjects’ favor. He twice lowered taxes, and he distributed food from his royal supplies during a famine. He built public works facilities and the cities of Caesarea, Haifa, and Sebaste (Samaria). And he erected protective palace-fortresses such as Masada, Herodium, and Caesarea Maritima.

But his most significant project to appease the Jews was rebuilding Solomon’s temple. Typical of everything he did, Herod built the temple larger than Solomon ever had. He made it the most beautiful building in all of Judea by embellishing it with an abundance of gold. And on one corner of the temple, Herod built Antonia, another protective fortress, though Roman soldiers often used it to keep an eye on any possible rebels.

[READ MORE ABOUT THE TEMPLE’S CONSTRUCTION: King Herod and His Magnificent Temple]

Despite his outreach efforts, his declining mental and physical health led him to become increasingly cruel. Some psychologists suspect he had paranoid schizophrenia. More recently, psychological researchers say he suffered specifically from Paranoid Personality Disorder (Kasher and Witztum 2007:431).

Herod was not alone in his condition. It seems mental disorders ran through the family.

All in the Family

Herod had three siblings—brothers Phasael and Pheroras and sister Salome. Phasael committed suicide soon after the Parthians captured him in 40 B.C. His other brother, Pheroras, and his sister, Salome, were every bit as devious as Herod. Both continually attempted to claim power throughout Herod’s tumultuous life.

Pheroras plotted with Salome and their nephew, Antipater (Grandfather Antipater’s namesake and Herod’s oldest son), to spread rumors in the hope of pushing Antipater’s siblings out of favor with Herod (see below). Meanwhile, Salome used her brother’s mental instability to deceive him into thinking his beloved Mariamne was unfaithful to him. Sadly, Herod believed his sister and had Mariamne, her two sons, brother, and grandfather all executed.

Herod had eight other wives beside Doris, his first wife, and Mariamne. But his love for Mariamne surpassed them all. After her death, Herod became quite depressed and was known to indulge in long bouts of drinking, which further affected his health enough to force him to bed.

While he dealt with his condition, Mariamne’s mother, possibly in cahoots with and perhaps at Solome’s urging, attempted to take Herod’s power. But Herod heard of it and had her executed too.

Herod’s palace-fortress Masada

Salome’s Deceit

Over the next ten years, Judea experienced a time of peace and prosperity under Herod’s rule. But his family legacy became quite convoluted. Altogether, Herod had 14 children. He appointed several of them to places of power, where they continued their father’s cruel methods of governing.

Two of Herod’s sons, Alexander and Aristobulus, were Herod’s favorites (Mariamne was their mother). The brothers’ favor with Herod and the community caused a great deal of jealousy in Antipater, Pheroras, and Salome (again). They conspired against the two brothers and incited their rivals’ anger, causing false accusations of treason. Herod finally gave in to the pressure to pursue justice. With the emperor Augustus Caesar’s permission, he had his sons tried before a Roman tribunal, where the two brothers were pronounced guilty and summarily executed in 7 B.C.

Meanwhile, Antipater fell out from his alliance with Uncle Pheroras and Aunt Salome, who did not like that he was designated Herod’s heir apparent instead of her son. When Pheroras was mysteriously poisoned, signs seem to point to Salome convincing Herod that Antipater was the perpetrator. So, Herod recalled him from Rome, had him tried and convicted, and sent him to prison to await execution.

Herod Splits His Kingdom

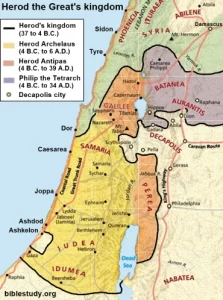

During this time, Herod’s overall health continued to decline while his insane jealousy continued to grow. As Antipater sat in prison, Herod changed his will to make his other son, Antipas, the heir apparent. However, soon after Herod had Antipater executed, he changed his will again, splitting his kingdom among his remaining sons. He even left a portion to his greedy sister.

And so Herod Archelaus was named king of Judea, and Herod Antipas became the lesser-titled tetrarch of Galilee and Perea (just south of Galilee). Their half-brother Herod Philip was appointed tetrarch of the areas north and west of the Sea of Galilee, a mainly poor Gentile area. Luke 3 confirms that Herod Philip did control these areas.

“Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, Herod [Antipas] being tetrarch of Galilee, his brother, [Herod] Philip tetrarch of Iturea and the region of Trachonitis….” (Luke 3:1)

Herod gave Salome a small portion along the Mediterranean coast, which she briefly ruled until 10 A.D., and the remaining areas came under the Syrian governor’s jurisdiction.

Massacre of the Innocents

For Bible readers, the expansion of Herod’s kingdom is not what they know best about him. He is better known as the author of “the massacre of the innocents,” found in Matthew 2, which occurred shortly after the Magi visited Joseph, Mary, and their newborn son, Jesus.

“Then Herod, when he saw that he was deceived by the wise men, was exceedingly angry. And he sent forth and put to death all the male children who were in Bethlehem and in all its districts, from two years old and under, according to the time which he had determined from the wise men.” (Matthew 2:16-17)

Some people speculate the massacre is just folklore or legend, not an actual historical event. It is only mentioned in Matthew 2 and nowhere else in the Bible. But since we know the Bible is God’s inerrant, holy word and thoroughly true (2 Timothy 3:16), we can trust it did occur at some point, though the exact date is unknown.

As such, it seems Herod’s massacre may have occurred sometime while he dealt with all the issues he had with his sons and before he carved up his kingdom, though there is no solid evidence.

Herod Antipas, not the Great

Herod’s madness and family greed were not the only problems in the family. Incest and infidelity were also common.

Herod’s son, Herod II, married his paternal niece, Herodias. Together, they had a daughter named Salome (the second Salome in the family). Eventually, Herodias left Herod II and married her other uncle, Antipas (though the book of Matthew says she married her other uncle, Philip). The topic is a bit controversial among scholars. Regardless, John the Baptist condemned the marriage, so Herodias schemed to have him beheaded.

“For Herod had laid hold of John and bound him and put him in prison for the sake of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife. Because John had said to them, ‘It is not lawful for you to have her.'” (Matthew 14:3-4)

The verses about John’s death in Matthew 14 (also Mark 6) mention Herod, but they refer to Herod Antipas and not Herod the Great. Antipas was also the Herod who tried Jesus and placed a beautiful robe on Him the night before the Lord’s crucifixion.

“Then Herod, with his men of war, treated [Jesus] with contempt and mocked Him, arrayed Him in a gorgeous robe, and sent Him back to Pilate.” (Luke 23:11)

Herodias and her daughter, Salome, with their prize–John the Baptist’s head

The Madness Continues

Matthew 14 also mentions Herodius’ daughter dancing at Antipas’ birthday party. The daughter was Salome, Herodias’s daughter, by her first husband, Herod II.

When Salome grew up, she married her Uncle Philip. She later married her cousin Aristobulus, Herod the Great’s grandson through his oldest son, Antipater III.

Herod’s son Aristobulus (not the one married to Salome, as just mentioned) married and had two sons, Agrippa I and Agrippa II. Agrippa I also had incestual relations. He married his cousin Cypros, his uncle Phasael’s granddaughter.

Likewise, Aristobulus’ other son, Herod of Chalcis (present-day Lebanon), married his niece Bernice, Agrippa I’s daughter. After Chalcis died, she moved in with her brother, Agrippa II, with whom it is rumored she had sexual relations.

Both history and the Bible prove that madness and general mental volatility ran deep in Herod’s family, causing political, cultural, and religious instability throughout Judea. Yet, Israel continued to thrive and survive under God’s protection and grace.

As for Herod, his dynasty finally ended in 93 A.D. after the death of Agrippa II, who never married or had children. And the rest, as they say, is history.