!["[Then] Herod the king stretched out his hand to harass some from the church." (Acts 12:1)](https://www.steppesoffaith.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Herod-harassed-the-church-Acts12.1-300x300.jpg)

“[Then] Herod the king stretched out his hand to harass some from the church.” Acts 12:1

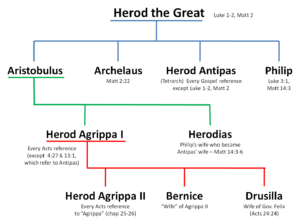

“Herod” appears many times in the gospels and the book of Acts, but it does not always refer to the same man. In fact, the Bible mentions six different men named Herod.

The most popularly known Herod is Herod the Great. He famously appears in the gospels of Matthew and Luke in the story of Jesus’ birth. Luke only mentions that Jesus was born “in the days of Herod, king of Judea” in Luke 1:5. However, Matthew provides more information.

Matthew 2 details the wise men traveling from the East to Jerusalem, following a star. Upon arriving in town, they visit King Herod’s palace to inquire about the promised Messiah’s whereabouts.

“Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we have seen His star in the East and have come to worship Him.” (Mt 2:2)

Herod becomes enraged at the news. When the wise men did not return to tell him where Jesus was, he ordered all male boys under the age of two killed (Mt 2:16) in an event now known as “The Slaughter of the Innocents.” Providentially, he did not kill Jesus because God had directed Joseph in a dream to take his young family and flee to Egypt (Mt 2:13-15).

The Bible does not mention more about Herod the Great, but historical sources detail his lust for power and fame. He implemented opulent building programs across Judea, including the reconstruction of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem and Masada, his lavish clifftop refuge overlooking the Dead Sea.

Herod was also known for his extreme acts of brutality, sometimes against his own family members. Some scholars attribute his bizarre behavior to possible schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s disease. He was highly skeptical of anyone he presumed to be disloyal, including his wife, Mariamne. He loved her dearly, but because he suspected her of unfaithfulness, he charged her with treason and executed her in 29 B.C. He fell into a great depression after her death and turned to alcohol for solace, which soon caused him to be bedridden. His poor health tempted his mother-in-law, Alexandra, to seize the opportunity to overtake his throne, but he heard of her scheme and had her put to death as well.

Aside from Mariamne, Herod also married Doris, Malthace, Cleopatra of Jerusalem, and another Mariamne, plus five other women. Among them, Herod had six sons and three grandsons, five of which were also named Herod: Archelaus, Antipas, Philip, Agrippa I, and Agrippa II.

Herod Archelaus

Herod had four sons during his first three marriages. However, each son was either executed or disinherited. By his fourth marriage to a Samaritan woman named Malthace, he produced two more sons—Antipas and his older brother, Archelaus.

Born in 23 B.C., Archelaus inherited his deceased father’s entire kingdom (except for Galilee, most notably) in 4 B.C. The Bible only mentions Archelaus in Matthew 2:22 when Joseph hears the news of Herod the Great’s death.

“But when [Joseph] heard that Archelaus was reigning over Judea instead of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there. And being warned by God in a dream, he turned aside into the region of Galilee. And he came and dwelt in a city called Nazareth.” (Mt 2:22-23)

Archelaus was a proverbial “chip off the old block.” Of all of Herod the Great’s sons, he was the most vicious. Soon after assuming power, he slaughtered 3,000 people in Jerusalem during a rebellion led by a shepherd who sought the throne. He also murderously quelled another rebellion led by students who destroyed a golden eagle that Rome ordered mounted over the temple’s entrance (an enormous offense to Jews).

Archelaus so enraged his constituents that a delegation of Jews and Samaritans brought charges against him. Emperor Augustus summoned Archelaus to Rome and subsequently deposed and banished him to Gaul (eastern Europe) in 6 A.D. Archelaus’ kingdom was reduced to a province and placed under the rule of a Roman prefect (governor) chosen from the royal equestrian class.

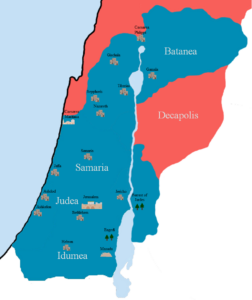

Herod Archelaus, Antipas, and Philip’s territories.

His Brother Antipas

Archelaus shared his father’s kingdom with his younger brother, Antipas, who controlled Galilee in the north and Perea in the east.

Antipas continued his father’s building program, including his new capital, Tiberias, which he illegally built on an old Jewish cemetery and decorated with animal figures. Antipas’ selfishness caused much unrest among the people, especially his divorce from his first wife to marry his half-brother’s (Philip) wife, Herodias. The unscrupulous marriage prompted a border war with his first wife’s father, King Aretas of Nabatea (Antipas lost).

The marriage also irritated John the Baptist, who confronted the tetrarch in Mark 6.

“For Herod himself had sent and laid hold of John and bound him in prison for the sake of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife, for he had married her. Because John had said to Herod [Antipas], ‘It is not lawful for you to have your brother’s wife.’“ (v17-18)

Antipas feared John (Mk 6:20) and did not want to stir the people’s anger further. However, Herodias took great offense and devised an evil scheme to trick Antipas into executing John during her husband’s birthday feast. Her plan succeeded, and Antipas killed John with immense regret (Mt 14:3-11, Mk 6:21-28, and Lk 9:7-9).

Antipas also met Jesus. Following a sham trial by the Sanhedrin, the Jewish leaders brought Jesus to Pilate, who sent Him to Antipas since he was the ruler of Galilee. Luke 23:8-11 describes Antipas as being eager to see Jesus and asking many questions, but the Lord refused to answer. As a result, Antipas made offensive jokes about Jesus, wrapped an old royal robe around Him, and sent Him back to Pilate for final judgment.

Several years after Jesus’ death and resurrection, Caligula came to power in Rome. He granted Antipas’ brother-in-law/nephew, Agrippa I, the title of king over certain areas bordering Galilee. Feeling jealous, Antipas traveled to Rome to seek the same title. However, Agrippa accused his uncle of treason against the emperor. Two years later, Caligula deposed Antipas, exiled him to southern France, and granted his land to Agrippa.

Herod Philip

When Herod the Great died, he split his kingdom among three sons—Archelaus, Antipas, and Philip, the tetrarch. Herod Philip reigned over areas northeast of Galilee inhabited mainly by Gentiles. Matthew 14:3 mentions Philip in the story of John the Baptist’s tragic death.

“For Herod had laid hold of John and bound him and put him in prison for the sake of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife.”

Recall that Herodias married Antipas, but her first husband was her uncle Philip, Antipas’ half-brother. The move prompted John the Baptist to criticize the marriage and Herodias to respond in vengeance (Mk 6:17-18).

Philip reigned in peaceful times and completed two significant building projects. First, he enlarged a small city near the headwaters of the Jordan River and renamed it Caesarea Philippi, where Paul later spent many days during his missionary journeys. Peter also professed that Jesus is the Messiah in this city (Matt 16:13; Mk 8:27; Lk 9:18), and Jesus proclaimed Peter to be the rock on which the budding church would grow (Matt 16:18).

Philip’s other considerable construction project was the ancient town of Bethsaida near the Sea of Galilee. Once a small fishing village, Philip updated, enlarged, and renamed it Julias. Modern Israeli maps still label it Bethsaida, but it is better known as et-Tell or el-Ajar. This city is where Jesus fed the 5,000 and restored the sight of the blind man (Mk 8:22-26).

Philip never remarried after Herodias’ divorce and died without heirs in 34 B.C.

Herod Agrippa I’s territory.

Herod the Great’s Grandson, Agrippa I

Recall that Herod the Great was known for his violence against his family members. One such victim was his son, Aristobulus, who had a son named Agrippa. Following his father’s death, the family sent Agrippa to Rome to pursue his education. He made a critical friend and ally there—the future evil Emperor Caligula.

Once in power, Caligula named Agrippa king over Lysanias (near Damascus) and his Uncle [Herod] Philip’s former tetrarchy. Three years later, he also became the tetrarch of his Uncle [Herod] Antipas’ territories. After Caligula’s assassination, Agrippa helped Claudius come to power, who rewarded Agrippa by giving him the additional provinces of Judea and Samaria. Ultimately, he came to rule over the same territory as his grandfather, Herod the Great.

Because former Emperor Tiberius once briefly imprisoned him, and he had run up numerous debts, Agrippa had an unstable relationship with Rome. To protect himself, he sought favor with the Jewish community by persecuting the early Christian church.

“Now about that time, Herod [Agrippa] the king stretched out his hand to harass some from the church. Then he killed James, the brother of John, with the sword. And because he saw that it pleased the Jews, he proceeded further to seize Peter also.” (Acts 12:1-3)

At 54, Agrippa I died suddenly following a public appearance in which the crowd proclaimed him a god. Acts 12:23 (as well as Josephus the historian) describes his untimely death as divine punishment from God for his excessive pride.

“Then immediately an angel of the Lord struck him because he did not give glory to God. And he was eaten by worms and died.”

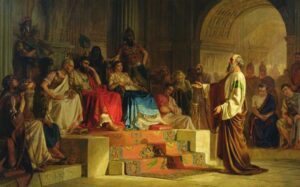

Paul on trial before Herod Agrippa II and Procurator Festus.

Agrippa II

The youngest and last Herod was Agrippa II.

Like his father, Herod Agrippa II grew up in Rome. He was 17 years old when his father abruptly died, too young to rule over a kingdom. However, by 23, his father’s friend, Emperor Claudius, granted him the small territory of Chalcis (present-day Lebanon), taking over from his uncle whom the Bible does not mention—Herod of Chalcis. Three years later, he surrendered Chalcis to inherit his great uncle Herod Philip’s tetrarchies. By the time Nero came to power, Agrippa II also controlled his great uncle Antipas’ previously held portions of Galilee and Perea.

However, unlike his father, Agrippa II was friendly toward the Jews in Jerusalem, including making expensive improvements to the temple. Still, he was always loyal to Rome.

Acts 25 and 26 record how Agrippa II and procurator Festus were involved in judging the apostle Paul’s case after his arrest for allegedly inciting a riot. After Paul testified about his faith in Jesus, Agrippa II judged Paul innocent and not deserving of death or imprisonment.

“Then Agrippa said to Paul, ‘You almost persuade me to become a Christian.’” (Acts 26:28)

But Paul had already appealed to Caesar, so Agrippa II handed him over to Rome for final judgment.

“Then Agrippa said to Festus, ‘This man might have been set free if he had not appealed to Caesar.’” (v32)

Agrippa II’s only romantic relationship was an incestuous one with his sister, Bernice. Therefore, he never married or had children, making his death in 93 A.D. the end of the Herodian dynasty.

The numerous mentions of Herod in the New Testament can be confusing since they are all recorded as “Herod.” But by studying biblical history, we can better discern which Herod is which and how each of them influences the gospel narratives and the early church.